August 12, 2007

The New York Times

The Man Who Set Film Free

By MARTIN SCORSESENINETEEN-SIXTY-ONE ... a long time ago. Almost 50 years. But the sensation of seeing “L’Avventura” for the first time is still with me, as if it had been yesterday.

Where did I see it? Was it at the Art Theater on Eighth Street? Or was it the Beekman? I don’t remember, but I do remember the charge that ran through me the first time I heard that opening musical theme — ominous, staccato, plucked out on strings, so simple, so stark, like the horns that announce the next tercio during a bullfight. And then, the movie. A Mediterranean cruise, bright sunshine, in black and white widescreen images unlike anything I’d ever seen — so precisely composed, accentuating and expressing ... what? A very strange type of discomfort. The characters were rich, beautiful in one way but, you might say, spiritually ugly. Who were they to me? Who would I be to them?

They arrived on an island. They split up, spread out, sunned themselves, bickered. And then, suddenly, the woman played by Lea Massari, who seemed to be the heroine, disappeared. From the lives of her fellow characters, and from the movie itself. Another great director did almost exactly the same thing around that time, in a very different kind of movie. But while Hitchcock showed us what happened to Janet Leigh in “Psycho,” Michelangelo Antonioni never explained what had happened to Massari’s Anna. Had she drowned? Had she fallen on the rocks? Had she escaped from her friends and begun a new life? We never found out.

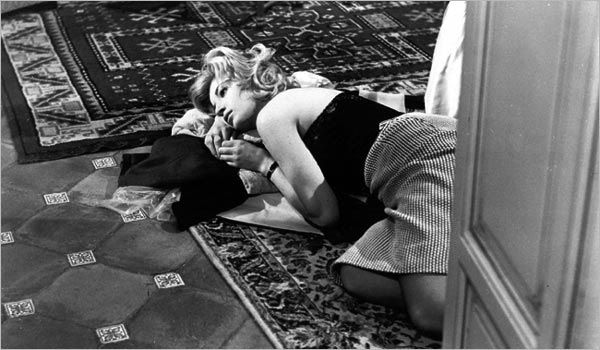

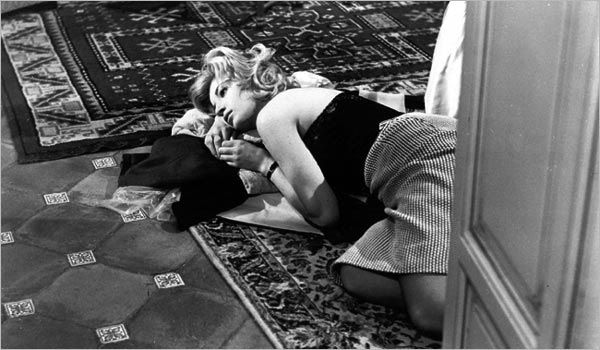

Instead the film’s attention shifted to Anna’s friend Claudia, played by Monica Vitti, and her boyfriend Sandro, played by Gabriele Ferzetti. They started to search for Anna, and the picture seemed to become a kind of detective story. But right away our attention was drawn away from the mechanics of the search, by the camera and the way it moved. You never knew where it was going to go, who or what it was going to follow. In the same way the attentions of the characters drifted: toward the light, the heat, the sense of place. And then toward one another.

So it became a love story. But that dissolved too. Antonioni made us aware of something quite strange and uncomfortable, something that had never been seen in movies. His characters floated through life, from impulse to impulse, and everything was eventually revealed as a pretext: the search was a pretext for being together, and being together was another kind of pretext, something that shaped their lives and gave them a kind of meaning.

The more I saw “L’Avventura” — and I went back many times — the more I realized that Antonioni’s visual language was keeping us focused on the rhythm of the world: the visual rhythms of light and dark, of architectural forms, of people positioned as figures in a landscape that always seemed terrifyingly vast. And there was also the tempo, which seemed to be in sync with the rhythm of time, moving slowly, inexorably, allowing what I eventually realized were the emotional shortcomings of the characters — Sandro’s frustration, Claudia’s self-deprecation — quietly to overwhelm them and push them into another “adventure,” and then another and another. Just like that opening theme, which kept climaxing and dissipating, climaxing and dissipating. Endlessly.

Where almost every other movie I’d seen wound things up, “L’Avventura” wound them down. The characters lacked either the will or the capacity for real self-awareness. They only had what passed for self-awareness, cloaking a flightiness and lethargy that was both childish and very real. And in the final scene, so desolate, so eloquent, one of the most haunting passages in all of cinema, Antonioni realized something extraordinary: the pain of simply being alive. And the mystery.

“L’Avventura” gave me one of the most profound shocks I’ve ever had at the movies, greater even than “Breathless” or “Hiroshima, Mon Amour” (made by two other modern masters, Jean-Luc Godard and Alain Resnais, both of them still alive and working). Or “La Dolce Vita.” At the time there were two camps, the people who liked the Fellini film and the ones who liked “L’Avventura.” I knew I was firmly on Antonioni’s side of the line, but if you’d asked me at the time, I’m not sure I would have been able to explain why. I loved Fellini’s pictures and I admired “La Dolce Vita,” but I was challenged by “L’Avventura.” Fellini’s film moved me and entertained me, but Antonioni’s film changed my perception of cinema, and the world around me, and made both seem limitless. (It was two years later when I caught up with Fellini again, and had the same kind of epiphany with “8 ½.”)

The people Antonioni was dealing with, quite similar to the people in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s novels (of which I later discovered that Antonioni was very fond), were about as foreign to my own life as it was possible to be. But in the end that seemed unimportant. I was mesmerized by “L’Avventura” and by Antonioni’s subsequent films, and it was the fact that they were unresolved in any conventional sense that kept drawing me back. They posed mysteries — or rather the mystery, of who we are, what we are, to each other, to ourselves, to time. You could say that Antonioni was looking directly at the mysteries of the soul. That’s why I kept going back. I wanted to keep experiencing these pictures, wandering through them. I still do.

Antonioni seemed to open up new possibilities with every movie. The last seven minutes of “L’Eclisse,” the third film in a loose trilogy he began with “L’Avventura” (the middle film was “La Notte”), were even more terrifying and eloquent than the final moments of the earlier picture. Alain Delon and Ms. Vitti make a date to meet, and neither of them show up. We start to see things — the lines of a crosswalk, a piece of wood floating in a barrel — and we begin to realize that we’re seeing the places they’ve been, empty of their presence. Gradually Antonioni brings us face to face with time and space, nothing more, nothing less. And they stare right back at us. It was frightening, and it was freeing. The possibilities of cinema were suddenly limitless.

We all witnessed wonders in Antonioni’s films — those that came after, and the extraordinary work he did before “L’Avventura,” pictures like “La Signora Senza Camelie,” “Le Amiche,” “Il Grido” and “Cronaca di un Amore,” which I discovered later. So many marvels — the painted landscapes (literally painted, long before CGI) of “Red Desert” and “Blowup,” and the photographic detective story in that later film, which ultimately led further and further away from the truth; the mind-expanding ending of “Zabriskie Point,” so reviled when it came out, in which the heroine imagines an explosion that sends the detritus of the Western world cascading across the screen in super slow motion and vivid color (for me Antonioni and Godard were, among other things, truly great modern painters); and the remarkable last shot of “The Passenger,” where the camera moves slowly out the window and into a courtyard, away from the drama of Jack Nicholson’s character and into the greater drama of wind, heat, light, the world unfolding in time.

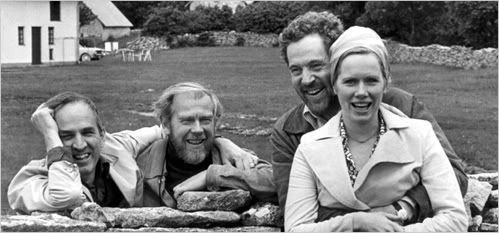

I crossed paths with Antonioni a number of times over the years. Once we spent Thanksgiving together, after a very difficult period in my life, and I did my best to tell him how much it meant to me to have him with us. Later, after he’d had a stroke and lost the power of speech, I tried to help him get his project “The Crew” off the ground — a wonderful script written with his frequent collaborator Mark Peploe, unlike anything else he’d ever done, and I’m sorry it never happened.

But it was his images that I knew, much better than the man himself. Images that continue to haunt me, inspire me. To expand my sense of what it is to be alive in the world.